“Slow productivity” sounds like an oxymoron, but it’s actually the title of Cal Newport’s latest book. Though it isn’t a Christian book, I think many of the principles of Slow Productivity square quite well with a Christian philosophy of personal productivity.

Newport is responding to the frenetic, anxious busyness that assaults the modern knowledge worker. He describes our battles with overcommitment and burnout not as a symptom of trying to be too productive, but as a consequence of us practicing “pseudo productivity.” Pseudo-productivity is when we use “visible activity as the primary means of approximating actual productive effort” (Page 22).

In other words, we like to pretend that busyness is the same thing as actually getting important things done. The solution, Newport says, is embracing slow productivity, a philosophy consisting of three simple principles:

- Do fewer things

- Work at a natural pace

- Obsess over quality

While Newport is not a believer, I think Christians can glean much wisdom from his three principles, which square well with biblical anthropology and bringing an eternal mindset to how we steward our lives and work.

1. Do Fewer Things

Most of us first get into personal productivity because we want to increase our capacity to handle a growing workload and its attendant stress. So, the call to simply “do fewer things” might not seem like a solution to our problem. But don’t dismiss this point too quickly. As Newport shows, most of us are busy and overwhelmed because we are choosing to stay busy instead of doing the much harder thing: identifying the few most important things and working on them with extreme focus.

This concept is very closely related to Newport’s three benefits that he outlines in Deep Work. He says deep work is valuable, rare, and meaningful. And the only way you can accommodate deep work is by drastically narrowing down the total number of things you do.

Newport says the goal of personal productivity isn’t to do more things but rather to produce more value. Not every activity has equal value, and in fact, sometimes, the more we do, the less value we create.

Working on fewer things can paradoxically produce more value in the long term: overload generates an untenable quantity of nonproductive overhead.

Slow Productivity, 97.

So, we need to prioritize and give more of ourselves to those few activities that produce the most value. The important thing we must add to this concept as believers is that we judge value on an eternal timeline.

2. Work at a Natural Pace

Newport not only calls us to do fewer things but also to work on them more slowly. Again, this flies in the face of pseudo-productivity, which emphasizes hustle over contemplation. Newport fleshes this out as he discusses approaching our lives “seasonally” (a concept I explore in The Myth of a Balanced Life).

for most of recorded human history, the working lives of the vast majority of people on earth were intertwined with agriculture, a (literally) seasonal activity. To work without change or rest all year would have seemed unusual to most of our ancestors. Seasonality was deeply integrated into the human experience.

Slow Productivity, 139.

Good things take time, and we are finite creatures in a world that has a season for everything (Ecclesiastes 3:1). Not everything needs to be rushed through. Our most important projects, especially creative work, thrive best when given time to breathe.

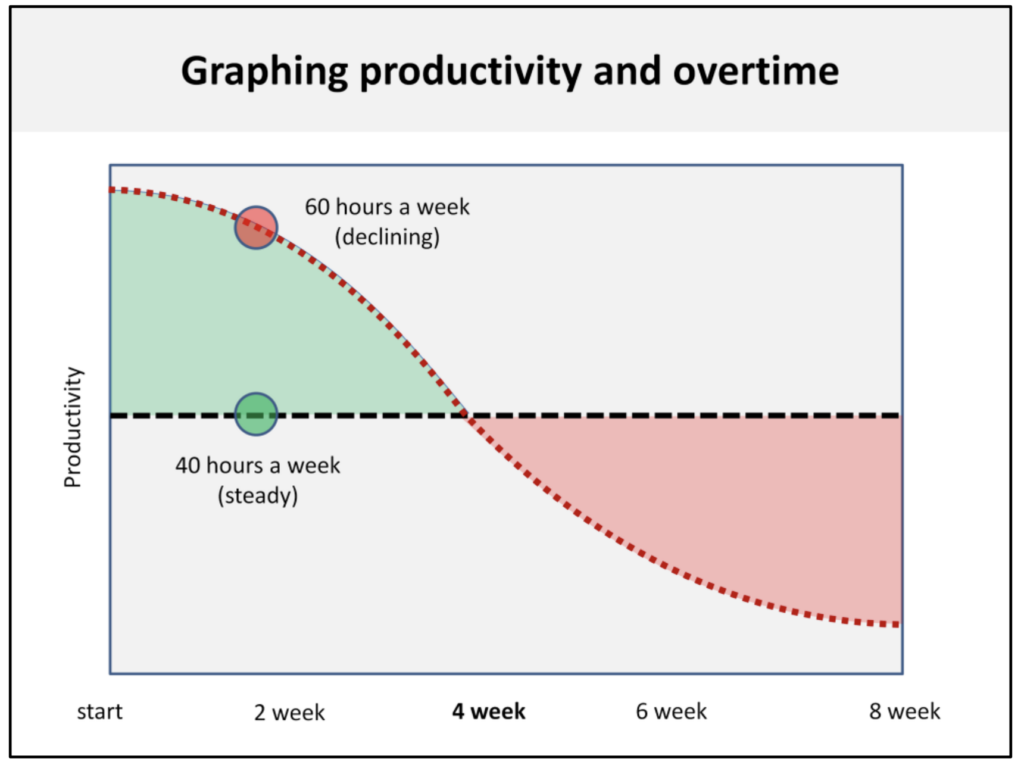

Certainly, there are times when we need to sprint, but if we constantly operate at an unsustainable pace, we actually experience a decrease in our productivity. The graph below, from Daniel Cook’s legendary 8 Laws of Productivity, illustrates this well. It shows how when people work more than 60 hours a week, in the short-term they will see an increase in productive output, but keep this up past 3–4 weeks, and it begins to negatively affect their productivity.

Again, this may seem like an impossible ideal, especially at work. What boss is going to be okay with you slowing down? But Newport offers many practical strategies for working toward a more natural pace. But it begins with you first developing the conviction that this slower pace is not just possible but necessary.

I would also hasten to add that living at an unsustainable pace can also be spiritually harmful to us. We reject our basic creatureliness when we work at an unnatural pace. We are trying to act like God. And this creates all kinds of problems for us. Francis Schaeffer captures this well,

“The basic psychological problem is trying to be what we are not, and trying to carry what we cannot carry. Most of all the basic problem is not being willing to be the creatures we are before the Creator.”

Francis Schaeffer, True Spirituality, 137.

To work at a natural pace isn’t an act of lazy self-indulgence; it’s a humble admission that we aren’t God.

3. Obsess Over Quality

Obsess over the quality of what you produce, even if this means missing opportunities in the short term. Leverage the value of these results to gain more and more freedom in your efforts over the long term.

Slow Productivity, 173.

Newport calls this principle the glue that holds it all together. This is a call to excellence and craftsmanship. I think this attitude fits so well with the heart of a Christian who is seeking to honor the Lord with their work. We don’t want to phone it in, do the bare minimum, or work just for a paycheck. We take our work seriously because we are working “not by way of eye-service, as people-pleasers, but with sincerity of heart, fearing the Lord” (Colossians 3:22).

If we prioritize quality work in our work, we will almost automatically slow down to a natural pace, and we will be forced to focus on fewer things. Again, this isn’t easy, but it is possible. If these concepts intrigue you, I encourage you to read the book for Newport’s implementation strategies.

It’s in this section that I found my favorite quote from the book. I actually wrote it on a notecard so I can be reminded of more often:

An Eternal Perspective on Productivity

At its heart, Slow Productivity is a call to work with a low-time preference. And this concept only becomes more powerful when we expand this timeline into eternity.

Several times while reading Slow Productivity I was reminded of Moses in Psalm 90, who prays, “So teach us to number our days that we may get a heart of wisdom.” (verse 12). When we think of eternity in relation to our short lives, it makes us desire to do those things that last. It produces an urgency to prioritize the lasting over the ephemeral.

And indeed, this is how the Psalm ends,

Let the favor of the Lord our God be upon us,

Psalm 90:17

and establish the work of our hands upon us;

yes, establish the work of our hands!

We want to produce work the value of which lasts into eternity. But we recognize that it’s He who will establish the work, not our frantic efforts. With this in mind, let’s focus on fewer things, slow down to a more reasonable pace, and strive for excellence in all we do. And let’s do it all for the glory of God.